Affiliate Disclosure: Automoblog and its partners may earn a commission when you use the services and tools outlined here for extended warranties, car shipping companies, and auto loan comparisons. These commissions come to us at no additional cost to you. See our Privacy Policy to learn more.

As the third quarter of 2023 approaches, the semiconductor shortage that began in 2020 is still having a broad impact on the automotive industry. Automakers around the globe have cut 2.82 million vehicles from their production schedules so far this year, partially due to the scarcity of chips, or semiconductor component products. While this is a substantial decrease in production cuts compared to previous years, it is a strong signal that the chip shortage – and supply chain issues that come with it – is far from over.

In 2022, the U.S. government passed the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) Act, in part to help alleviate the shortage issue and reduce the chance of future shortages. With the promise of federal subsidies on the way, companies have invested heavily into domestic chip production. But while those investments will likely take years to impact the supply chain, one company – Wolfspeed Inc. – was ahead of the curve and is already expanding production.

The CHIPS Act Has Sparked a Wave of Investment in Domestic Chip Manufacturing

President Joe Biden signed the CHIPS Act into law on August 9, 2022, more than a year after it was introduced in the House of Representatives. The law provides funding and incentives for companies to invest in domestic semiconductor manufacturing as part of an attempt to strengthen domestic supply and decrease reliance on international manufacturers.

Included in the law is $39 billion in subsidies for investments in U.S.-based chip manufacturing and $13 billion for workforce training and semiconductor research. The law also provides a 25% tax credit for spending on new manufacturing equipment.

Sources differ on the exact numbers, but by most accounts, passage of the CHIPS Act and anticipation of its passage have prompted significant domestic investments. The Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), a leading trade group, estimated that the CHIPS Act prompted $200 billion in investments across more than 50 projects between May 2020 and December 2022. The group predicted that those investments would create 44,000 new domestic jobs.

A more recent assessment from independent analyst Jack Conness estimated that the law has encouraged $151 billion in investments across 26 projects as of June 8. Conness said that the investments would create 21,400 jobs in the chip manufacturing industry.

Wolfspeed Leads the Pack in Domestic Semiconductor Manufacturing

In the build up to and wake of the CHIPS Act, investments have come from major companies such as Bosch, Texas Instruments, and Micron. Most of these investments have been in building new chip manufacturing plans, which are known as “fabs” within the industry. However, one company was already expanding its chip-manufacturing capabilities even before the CHIPS Act came into the picture.

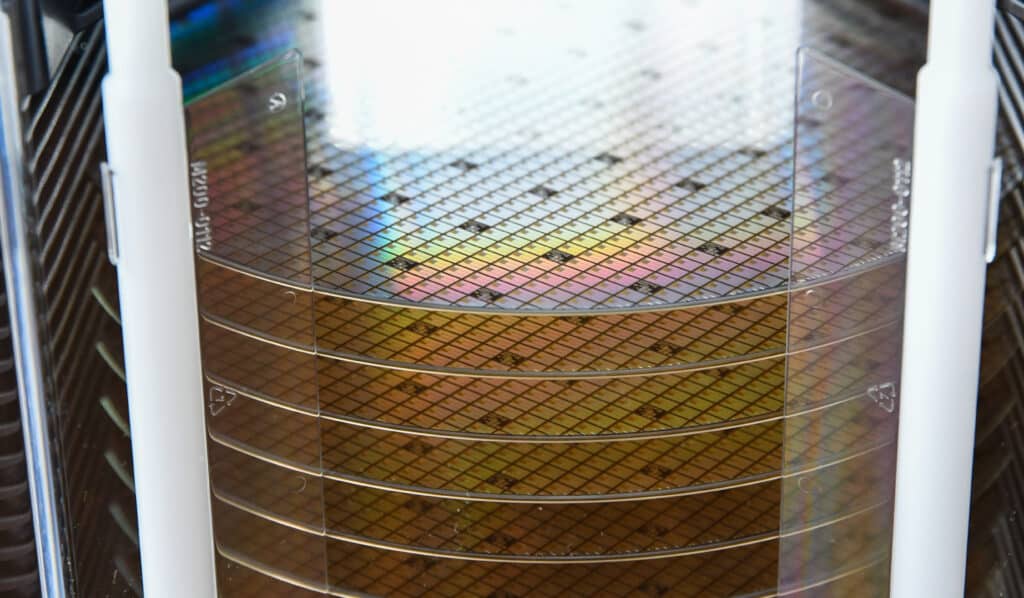

Based in Durham, North Carolina, Wolfspeed, Inc. got its start by developing a method for growing silicon carbide in a lab in 1987. The company, formerly known as CREE, released the world’s first commercial silicon carbide wafer in 1991. Today, Wolfspeed is the world’s largest producer of silicon carbide, accounting for 62% of the world’s supply produced for semiconductors.

Automoblog spoke to Lauren Kegley, automotive marketing manager for Wolfspeed’s Discrete Power Devices division, about the company’s role in the larger shift towards domestic production. She said that her team at Wolfspeed is pleased to see the push towards making more chips on U.S. soil.

“We’re excited to see people want to support more domestic manufacturing because we’ve prioritized that for a very long time,” said Kegley. “So as we continue to move forward, we’re really excited to continue to be a part of the CHIPS Act.”

Wolfspeed was already investing heavily in the industry well before the law was even a bill. In April 2022, the company opened a brand new chip plant in Mohawk Valley, New York as the chip shortage continued on.

“Our Mohawk Valley fab is the world’s first 200 millimeter silicon carbide facility,” said Kegley. “It’s also going to be the world’s largest silicon carbide manufacturing facility. It is a fabrication facility, so this is where we actually build the semiconductor devices.”

While the facility opened a year ago, Wolfspeed announced plans for its construction in 2019, a year before the chip shortage began. The new fab allows Wolfspeed to be its own final step in the semiconductor production process. With a critical shortage of semiconductors still in effect, the opening of the plant couldn’t have come at a more opportune time.

“It takes a long time to build new semiconductor fabrication capability, so we’re really excited to be ahead of this conversation,” Kegley said. “We announced our Mohawk Valley expansion well before the automotive chip shortage was a thing. So, Wolfspeed is specifically poised to really help our customers.”

Wolfspeed Is Preparing for Increased Demand in the Near Future

The Mohawk Valley fab isn’t the company’s only production investment, or even its biggest. Wolfspeed recently received a permit from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ) that allows it to begin construction on a $5 billion facility near Siler City, North Carolina, about an hour southeast of the company’s Durham headquarters.

The Siler City facility will produce silicon carbide wafers that will be sent to the Mohawk Valley fab to be made into completed semiconductors. Wolfspeed expects the facility to create 1,800 jobs by the end of 2030 and enable the company to greatly increase production capacity.

“The more we scale and the more we have availability, obviously the larger our production capacity is,” said Kegley. “That allows faster time to market for our customers because we begin to reduce that pressure and lead time.”

That additional capacity won’t just help alleviate supply shortages, it’s also likely to be necessary in the near future as demand for semiconductors increases. The average car in 2021 had around 1,200 semiconductor chips in it, roughly double the number of chips in the average car in 2010. That number is only likely to increase in the coming years as cars utilize more computer technology.

The rate of increase is likely to accelerate as electric vehicles (EVs), which use twice as many chips as internal combustion vehicles, continue to take over more of the auto market. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Global EV Outlook 2023, EVs accounted for just 4% of the overall car market in 2020. By 2022, they took up 14% of it.

The IEA estimates that EVs will claim 18% of the total auto market in 2023. And, according to WUNC, Wolfspeed and major automakers alike expect EVs to account for 30% of the market by 2030.

Improvement on the Horizon, But Semiconductor Shortage Remains

While Wolfspeed and other companies invest and prepare for future production needs, the current semiconductor shortage is still an issue for automotive manufacturers. Suppliers are still looking to fill backorders as demand continues to increase.

Sam Fiorani, automotive industry expert and vice president of Global Vehicle Forecasting at AutoForecast Solutions, told Automoblog that while there have been improvements in the semiconductor supply chain, the situation remains a challenge for the auto industry.

“More than two years later, automakers and suppliers have secured better sources of chips,” he said. “The problem isn’t completely solved, but it is better. Where shortages still exist, chips are being funneled to higher-profit, typically higher-priced models at the cost of mainstream, affordable vehicles.”

As to the question of when the chip shortage will end, Kegley says that Wolfspeed is in a good position due to its early investments in expansion.

“I’d say it’ll take months if we’re talking about Wolfspeed’s customers,” she said. “We’re going to be able to capitalize on the Mohawk Valley facility.”

Kegley said that Wolfspeed’s position, however, is unique. Predicting when the industry at large will bounce back is more difficult.

“It really depends on how big are the investments people are making in production,” she said. “How efficient is their manufacturing? How high are their yields and how good are they at bringing forward new facilities? It’s really hard to pinpoint a date.”

Although the CHIPS Act has incentivized companies to pour billions into building new fabs in recent years, it will take time for those facilities to start producing chips and the materials to make them. It took close to three years for Wolfspeed to open the Mohawk Valley facility after announcing its plans. Even on a reduced timeline, it will likely be the latter half of the decade before recent CHIPS Act-related investments will impact the supply chain.

“We’re really talking about several years until we see the impact of investments in new production capability,” said Kegley.

But while the chip shortage may have helped inspire the CHIPS Act, solving the shortage isn’t the law’s ultimate goal. The financial support and other incentives the law provides are aimed at strengthening domestic production and reducing reliance on international manufacturers and suppliers. Kegley said that this is a positive direction for the semiconductor industry and other industries that rely on it.

“People who are designing and building here in North America will have the ability to immediately leverage that without depending on international supply chain partners,” she said. “As we move forward, when we think about domestic supply chain advantages, we will have the additional resiliency of having the ability to maintain domestic production.”

The CHIPS Act may not have an immediate impact on the semiconductor shortage. But investments in domestic chip manufacturing from Wolfspeed and other companies, bolstered by government support, may help avoid a similar shortage in the future.