Blade Runner was released in 1982 and landed with a thud. It went nowhere at the box office, and only later picked up steam and a cult following when it was released on VHS. Set in a dystopian, grimy, crowded Los Angeles of 2019. Blade Runner showed us a future of environmental devastation and the slow, inexorable grinding down of humanity, one person at a time, in pursuit of the all-mighty dollar.

Like all great works of art, it raises some essential questions of what makes us human; how does a person maintain their humanity; why do we live and what is the point of this life; and is it okay to fall in love with a robot you’ve been having sex with?

Flying Cars & Blade Runner

Of Blade Runner’s many predictions – genetic engineering, super-scale architecture, and holographic manipulation to name only three – the one we are concerned with here at Automoblog is, of course, flying cars. And, as with most things flying car related, I give this an F grade for its accuracy in terms of a technology prediction. But . . . there’s some interesting caveats that go along with how they handled flying cars in the world of Blade Runner that make the entire idea potentially much more workable.

- Related: The Petersen Automotive Museum’s Hollywood cars exhibit.

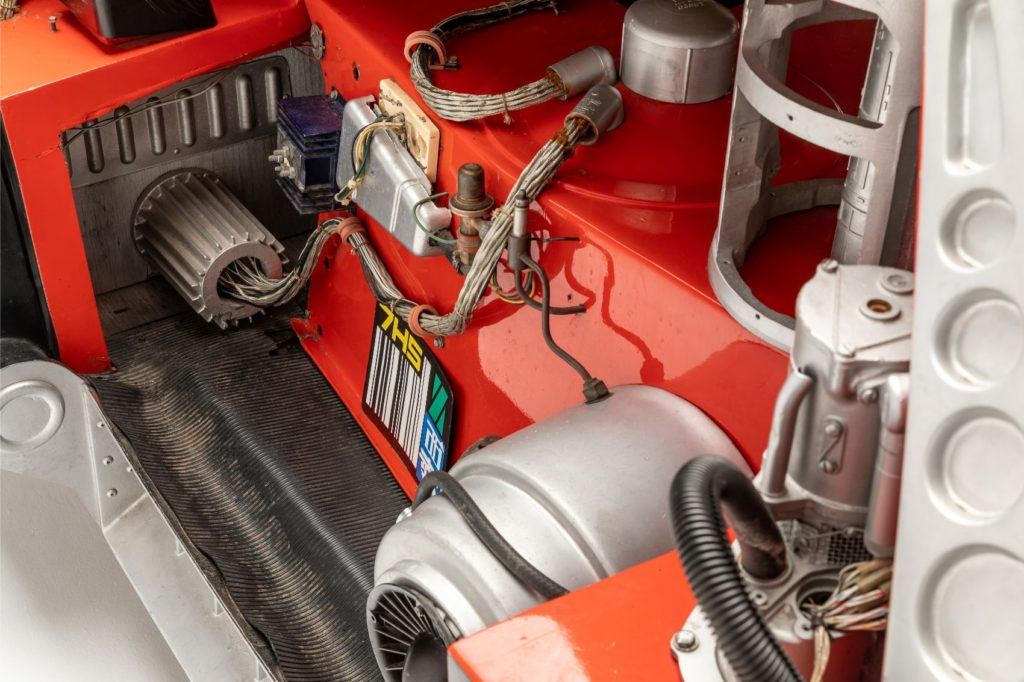

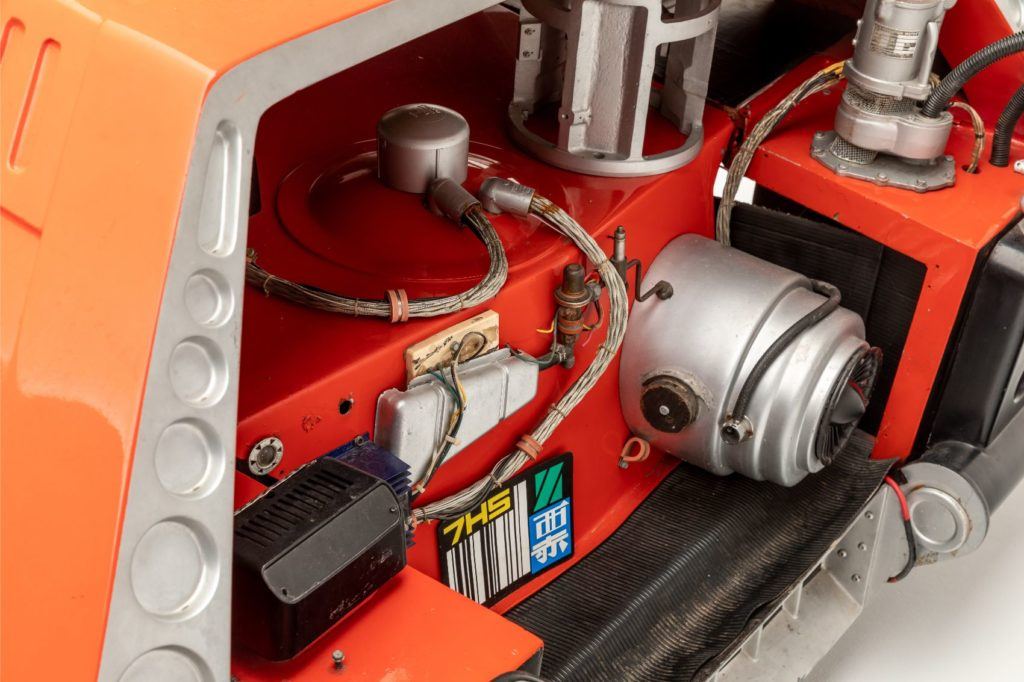

For starters, the flying cars, called “spinners,” were designed by the great Syd Mead, visual futurist, industrial designer, automotive designer, and all-around interesting human. He called his flying car an “aerodyne” that worked via an unseen propulsion system. Whatever was contained within the beetle-back of the spinner had enough power to both levitate and motivate it. How was never specified, but that was the basic idea. Director Ridley Scott was bright enough to hire just the right guy to work on his flying car concept.

Who Would Be Able To Use Flying Cars?

The other thing Blade Runner got right was who was using them. As far as I can tell (and I’ve seen this movie dozens and dozens of times), there are only two kinds of flying cars in the film. There are spinners that are flying police cars, and there was another model that looked like a private vehicle. The implication here is only the cops or wealthy elite get flying cars.

This greatly simplifies potential problems like overcrowded skies, accreditation of who gets to fly, and things of that nature. If there are only two kinds of people flying around our pollution-choked and congested cities – law enforcement and the rich – then there is an implication of a higher level of responsible use. In theory.

It’s also worth noting the amount of computer control and monitoring seen in the aerial use of a spinner. That would go a long way to mitigating a large number of problems.

Are The Flying Cars In Blade Runner Plausible?

Even though I gave the flying spinners in Blade Runner an F grade in terms of plausible technology, it is with those caveats. If there is a way to make flying cars work, we can’t just give them out will-nilly to any swell that desires one. We’d scrap the whole program within months due to fatal, smoking crashes and the inevitable lawsuits.

- Related: How close are we to flying cars and do we need them?

To put it another way, practically-speaking, I don’t see flying cars ever coming true. Police don’t need them, they’ve already got helicopters, and the same goes for the filthy rich with private planes. Sure, there are the half-loony innovators and ambitious companies out there still trying to make flying cars happen, but the landscape looks as bleak as the dust-choked desert consuming Las Vegas in the rather well-done follow-up, Blade Runner 2049. (Harrison Ford reprises his role).

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got to get down to Taffey Lewis’ place. I’ve got him on a line for drinks and I think I’ve got Sean Young’s number here somewhere.

Tony Borroz has spent his entire life racing antique and sports cars. He is the author of Bricks & Bones: The Endearing Legacy and Nitty-Gritty Phenomenon of The Indy 500, available in paperback or Kindle format. Follow his work on Twitter: @TonyBorroz.